A Buyer's Market: Book Club

An evening out that lasts 150 pages, THAT sugar incident, and a remarkable sex scene

Although I suspect this is not most people’s favourite book in Anthony Powell’s duodecad, it is an important one. Now bobbing along in the late 1920s, we get our first sighting of Magnus Donners (“the Chief”), Mr Deacon makes a lasting impression, Uncle Giles returns (hooray!), and Nick visits Stourwater in a visit that has some slightly sinister undertones. Also back is Widmerpool (“one of those symbolic figures, of whom most people possess at least one example, if not more, round whom the past and future have a way of assembling”) who takes another blow to the head in an echo of the banana incident in A Question of Upbringing, and whose father we learn was in the liquid manure business (Powell at his most cutting).

We also start to get more of a picture of Nick Jenkins himself, and I can’t say he comes out of book 2 with flying colours.

I’ve always been a big fan of the television series The Good Life, and rather like Dance I’ve had periodic rewatches every couple of decades. When I was young, I thought Tom Good was the bee’s knees, almost a role model. Now I’m older, he seems a bit of a self-centred pain, and it’s Jerry who feels much more likeable. Similarly with Nick, the first time I read the series I very much identified with him and thought he was a fine mixture of insouciance and perceptive observation.

But now I’m not so sure. Why, for example, is he courted by Sillery? Granted, he has some networking ability, but he never feels like he’s going to be a mover or shaker - he doesn’t have Stringham’s wealth and background, Truscott’s promise, or Donners’ pull, let alone Widmerpool’s get up and go. And why is he a popular invitee at dances? He doesn’t seem to say anything witty or penetrating, and often appears not to be that keen on the whole thing himself. "Why are you so stuck up?" Gypsy Jones, asks him, so it’s not just me that feels he’s hardly the merry jester of the party.

Which brings us on to what is easily the most memorable sex scene I’ve ever come across. If you’re not reading carefully, you might miss Nick and Gypsy getting together on the couch altogether, even though it runs to several pages. Some readers suggest this is when Nick loses his virginity, but even that’s not clear. I’m all for dignified reticence, but there’s circumspect and then there’s circumspect - if the Literary Review’s Bad Sex in Fiction Award had been running back in 1942, it would surely have won by a country mile. Additionally, Nick is hardly the gallant young chap when describing the event: “In fact, after the brief interval of extreme animation, her subsequent indifference, which might almost have been called torpid, was, so it seemed to me, remarkable.” And since I find Barmby unlikeable, Nick’s friendship with him means he’s slightly damned by association.

These issues aside I did enjoy some of the set pieces, especially Milly Andriadis’s party, and it’s always good to bump into Stringham hanging around the equivalent in my day of a kebab van. I also like the ambiguous element to the title of the book. A buyer’s market indeed, but who’s buying? Who’s selling? Are some people doing both? And what are they peddling? It’s certainly more of a meat market than an economic one.

And once again there’s plenty of Nick’s/Powell’s observations to keep you thinking. A few favourites:

“The illusion that egoists will be pleased, or flattered, by interest taken in their habits persists throughout life; whereas, in fact, persons like Widmerpool, in complete subjection to the ego, are, by the nature of that infirmity, prevented from supposing that the minds of others could possibly be occupied by any subject far distant from the egoist’s own affairs.”

“I used to imagine life divided into separate compartments, consisting, for example, of such dual abstractions as pleasure and pain, love and hate, friendship and enmity…As time goes on, of course, these supposedly different worlds, in fact, draw closer, if not to each other, then to some pattern common to all.”

and the inevitable ‘shaping of life’ themed reflection

“At that stage of life all sorts of things were going on round about that only later took on any meaning or pattern.”

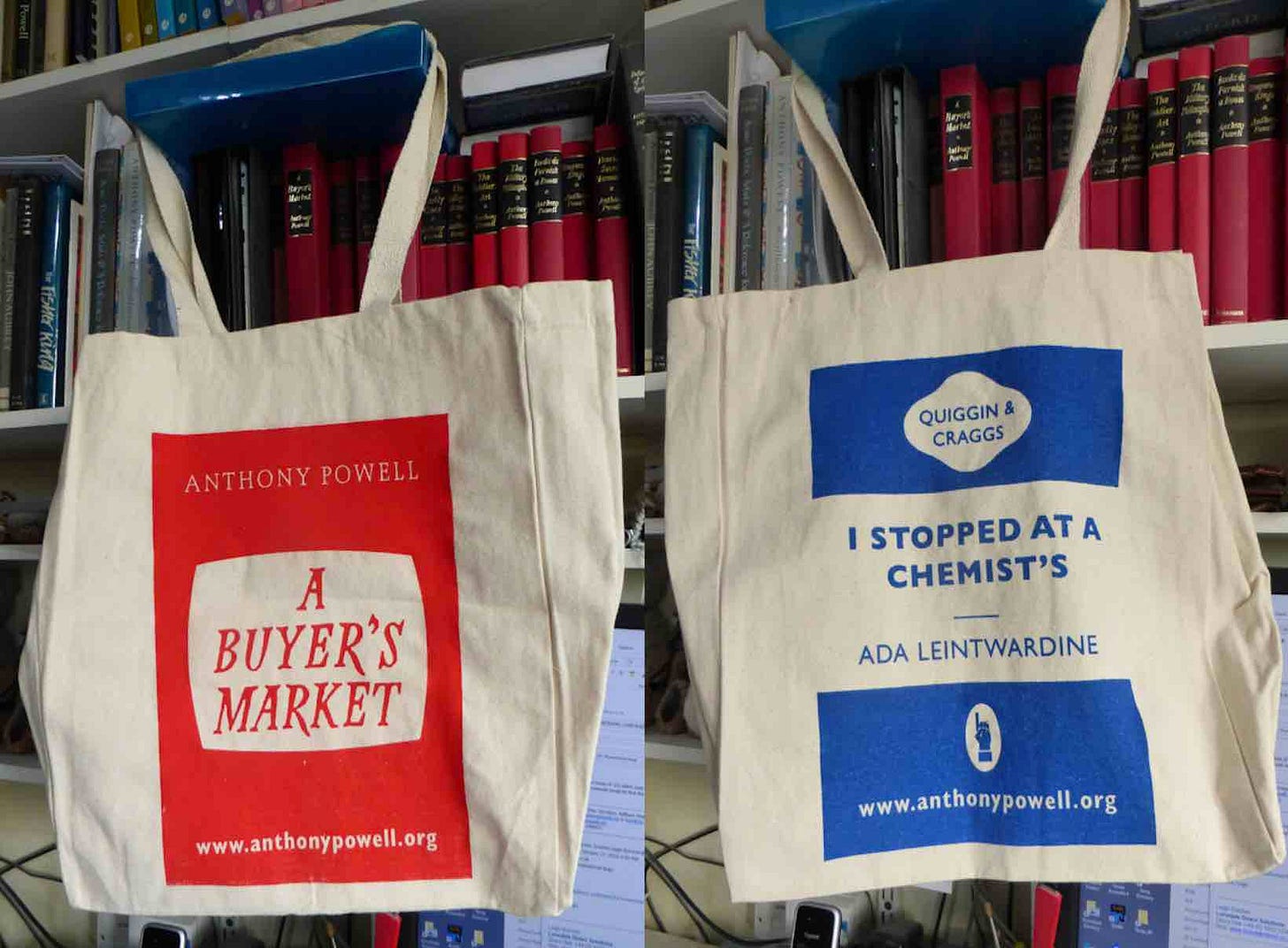

Two small points of note. I’m fond of Osbert Lancaster’s cover design for the Penguin edition which focuses on Milly’s party with the inimitable Max Pilgrim tickling the dominoes - Powell dedicated the book to Lancaster and his then wife Karen. Marc Boxer’s features Sillery and Prince Theodoric and is less to my liking. Also, the tote bag featured at the top of this newsletter is available only from the Anthony Powell Society. I can vouch for its durability.

Just finished it, somewhat late. Really interested in what Powell chooses to focus on here. Well over half of this book describes just one evening. In 12 books which span decades, he chooses to give over 5% of the whole series to describing just a few hours. But perhaps that’s exactly how one’s memory of the past is? One evening, even if it’s not dramatic for oneself, can linger in the mind (particularly when you are young), whereas weeks and months are just washed away by time’s ever-rolling stream. And individuals (like Deacon here) who, objectively, are not much more than bit players in your life, assume far greater significance for you than their role in it merits, and certainly more than than you do for them. Again, just like real life.

Thank you for encouraging me to one more read 'Dance to the Music of Time’.

These days I think I'm a far more analytical reader than I was when I read the books afresh in the 70s and 80s. On first reading, I think I was simply mesmerised by Powell's ability to keep a story going into twelve whole books. The extensiveness of the prose, the number of characters, the backdrop of politics, culture and society is impressive.

But now, your analysis has made me read the books in a different way.

Firstly, there is the prose style. By the time I got round to studying English literature at university, long sentences were rather frowned upon. By then novelists like Carver and Hemmingway had made short sentences - and short words – rather the vogue. But I found myself delighted to read Powell's narrative. It’s an object lesson in the use of punctuation and in the use of sometimes unusual, often long words – used as they should be used.

Here’s an example from book 2, chapter 1 - just after the sugar incident;

“It would, indeed, be hard to over-estimate the extent to which persons with similar tastes can often, in fact almost always, observe these responses in others: women: money: power: whatever it is they seek; while this awareness remains a mystery to those in whom such tendencies are less highly, or not at all, developed.”

Just for the sake of statistics, this sentence contains 54 words, four commas, one semi-colon and four colons!

I shall be interested to see if someone can come up with a more punctuation rich sentence – I’m sure there are many!

But whatever your views on grammar and punctuation, on spareness or complexity, I do think this sentence explains a lot about this particular book. It may possibly explain why the sentiments are expressed in one sentence.

Surely, in ‘A Buyer’s Market’ Powell is finding his own way in the world. If you like, he is toying with the relative attractiveness of women, money and power. He gives hints to the juxtaposition of different classes and political persuasions that have hovered in the background during his school days. Now, let loose on the world, he is sampling the offerings very different societies – and probably finding all of them wanting. His dalliance with the debutante Barbara shortly followed by the episode with Gypsy leave him unmoved by both their charms and their milieu.

I was particularly interested to read about his visits Mr Deacon’s antique shop, “west of Charlotte Street”, which he describes as a “nondescript ocean of bricks and mortar from which hospitals, tenements and warehouses gloomily manifest themselves in shapeless bulk among mean shops”. Fitzrovia was enjoying a bit of a heyday in the 30s. According to the internet, Dylan Thomas went to live there in 1934, the artist Augustus John haunted the pubs like The Wheatsheaf and The Fitzrovia Tavern. The proximity of the then new BBC broadcasting house created a drawn. Eventually intellectuals and artists such as Jacob Epstein, George Orwell and Aleister Crowley, as well as politicians like Nye Bevan and Michael Foot, went to live there. The Bloomsbury group of artists and writers actually lived in Fitzrovia around Fitzroy Square for a lot of this time.

Fitzrovia’s bohemian history is close to my heart. I have lived and worked since the early 80s in Great Titchfield Street, in a converted dress factory above a lighting showroom - how times have changed.

Fitzrovia in the thirties is an excellent location for Powell’s story. Being so centrally located, just North of Oxford Street, it is a stone’s throw from the smart set in Belgravia, from the political focus at Westminster, and close to London’s commercial and financial heart – the City of London. Fitzrovia in the thirties was about as close to a melting pot as existed in Britain at the time. What better place to imagine the mingling of different societies whose paths might never have met elsewhere.

Powell, in describing poor Nicholas’s unsatisfactory love life, is using a metaphor for the narrator’s lack of ambition, perhaps even his reluctance to come down on any side, or to take any stand. That’s why he does nothing when Widmerpool is so roundly insulted by Barbara. (Though he does immediately fall out of love with her). Perhaps he dares not speak up, for fear that he will find himself ostracised by the ‘bright young (rich) things he has learned to call his friends. But his forays to meet Deacon and his crowd suggest he is starting to question things.

In later books we see how the war breaks down these barriers of prestige and shakes up society, which will never be quite the same again. Nick doesn’t yet know whether he should pursue women, money or power. The final paragraphs of this book hint that Nick is finally growing up. This coming of age –an extended and uncomfortable period of life for him – will last quite a bit longer, before he will even be able to define his ‘Good Life’, let alone achieve it.