A Question of Upbringing: Book Club

Thoughts on the first volume of Anthony Powell's Dance to the Music of Time series

In the summer of 1988 just before I went to university I acted in the York Mystery Plays - there I am above, the second disciple from the left with dark hair, doing my very serious acting face at the lovely Victor Bannerjee as Jesus. It was a marvellous experience, surrounded by plenty of proper adults rather than teenagers for the first time in my life. Among them was the director Steven Pimlott, already a major name in opera and theatre, who was good enought to spend as much time with a nobody like me as he was with the star of the show.

I particularly remember a conversation with him during some down time in rehearsals when, with my vast and confident teenage knowledge of how exactly the world wagged, I had pooh-poohed his notion that coincidences reflected some kind of connected pattern in our lives and were not simply random and meaningless events. In a very fatherly and non-patronising way, Steven suggested that we have the same conversation in 20 years time to see if my thoughts had changed.

I’ve now read Anthony Powell’s opening novel of his 20th century epic three times and each time I’ve been strongly reminded of this conversation with him. Partly this is because there is no greater work of fiction that is founded on the theory that, as Patti Smith suggests, paths that cross will cross again.

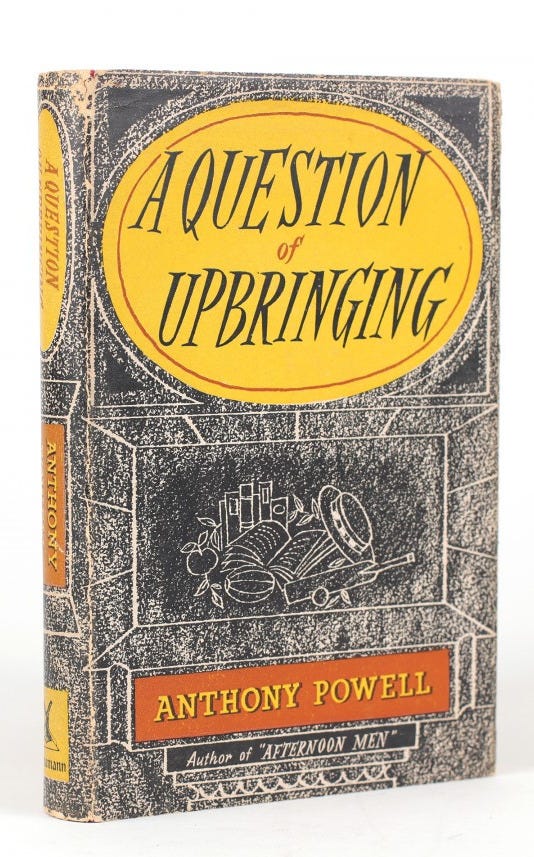

For those of you not taking part in the readathon I mentioned last month (although there’s plenty of time to join us and then add your thoughts in the comments below), this first part of the story introduces us to our mild mannered narrator Nick Jenkins at the sixth form in school (Eton, though it’s never explicitly named), enjoying a short break brushing up his language schools in France, and then at university (Oxford).

Even at this stage the cast list is quite lengthy, including his close school chum Stringham, school peer rather than pal the odd fish Widmerpool, and various thrusting young men and manipulative dons at Oxford. Plus his slightly black sheepish uncle, Giles (played in the 1997 television adaption by Edward Fox, an inspired piece of casting).

Although things do happen - a high spirited trick played by pupils on a teacher, a minor car accident, a crush on the sister of a schoolfriend, that slightly bemusing house stay in Touraine - from the start it is clear that this is not about what’s coming next, but who’s coming next, with Widmerpool unexpectedly popping up in France and Nick’s comment on Sunny Farebrother, whom he has only recently met, that “He piled his luggage, bit by bit, on to a taxi; and passed out of my life for some 20 years”. Indeed Powell sets out his stall on page 2, comparing our progress through life to Poussin’s painting of the Muses dancing:

“moving hand in hand in intricate measure, stepping slowly, methodically sometimes a trifle awkwardly, in evolutions that take recognisable shape: or breaking into seemingly meaningless gyrations, while partners disappear only to reappear again, once more giving pattern to the spectacle: unable to control the melody, unable, perhaps, to control the steps of the dance.”

It is not a spoiler to say that virtually everybody we meet in Upbringing reappears at some point in the story again, often, as Powell predicts above, in quite unexpected combinations or unlooked for moments. As in my previous readings, I was particularly sorry to see Stringham shimmer off.

I knew now that this parting was one of those final things that happen, recurrently, as time passes: until at last they may be recognised fairly easily as the close of a period. This was the last I should see of Stringham for a long time. The path had suddenly forked. With regret, I accepted the inevitability of circumstance. Human relationships flourish and decay, quickly and silently, so that those concerned scarcely know how brittle, or how inflexible, the ties that bind them have become.

The books are often broken down into four trilogies, and the first is very much a coming of age story. I think Powell captures Nick’s growing realisation that he’s got a very limited understanding of what’s going on around him very accurately - it’s certainly how I felt in my late teens and early 20s, surrounded by my own Stringhams and Widmerpools and crushes, including those encountered at the York Mystery Plays.

“Clearly some complicated process of sorting-out was in progress among those who surrounded me: though only years later did I become aware how early such voluntary segregations begin to develop; and of how they continue throughout life.”

Perhaps I feel a close bond to Nick because, like him (and indeed Powell), I am an only child, but I also love that while he has a remarkable ability to connect to the people who drift in and out of his life, he is by no means an all-seeing narrator, missing and misunderstanding things that the onlooking reader satisfyingly discerns. It would not be quite accurate to liken him to Forrest Gump, but he is something of Hildegard of Bingen’s “feather on the breath of God”.

Unlike many modern novelists who like to conjure historical atmosphere by namechecking events, fashions, and famous people, there is very little of that here, which I enjoy and feel adds to the slight feeling of timelessness. Although there are no dates in the books, commentators have worked out that Upbringing is set between 1921 and 1924, yet there’s no mention of the ongoing Anglo-Irish conflict, the BBC’s first radio broadcasts, the two general elections, or Spurs winning the FA Cup (#coys).

I also love Powell’s elegant writing style, the long sentences (semi-colons are his bread; and butter), the dry humour, the philosophical musings on aspects of life (which I often have to reread slowly to appreciate) and furious noddings of agreement when Nick makes comments such as “at that age I was not yet old enough to be aware of the immense rage that can be secreted in the human heart by cumulative minor irritation.” In fact I now wonder if my own writing which is dominated by similarly long sentence structure is an unconscious trait picked up from reading Powell at an impressionable age. It certainly annoyed the bejayus out of the old school hack who taught me at journalism college.

Two final brief bits and bobs:

by happy coincidence the fine folks at Neglectedbooks.com are also running a monthly reading group of Dance - they have also put together a page of contemporary reviews of Upbringing which are well worth a read

it’s already clear from this first volume that Powell loves his art and drops references to paintings throughout the series (when Nick compares Stringham to Alexander in Paolo Veronese’s ‘The Family of Darius before Alexander’ this is the painting he’s referring to, Alexander in the red tights) - Pictures in Powell does a terrific job in collating and explaining all of them

I never had that 20 years later conversation with Steven about the patterns of life because he sadly died far too early in 2007, a year younger than I am now. As well as discussing Dance, I think he would have been delighted to discover that he lived in the same tiny hamlet near Colchester where my brother-in-law has also lived for many years, and that I have recently got back in touch with one of the disciples who it turns out was at university with a close friend of mine. It’s a small world.

The February installment of Dance is ‘A Buyer’s Market’. Please do add your thoughts on Upbringing below.

Thank you for reintroducing me to these books. I managed to catch up and finished volume one this afternoon. I remembered from previous readings, and you have underlined this, that one has to take notice of all the characters mentioned so as to recollect

(Sorry. Sent the comment above by accident. )

….(so as to recollect) what one has previously been told about them when they reappear. I remembered much of book from before but with various omissions- I had quite forgotten about the French interlude.