Casanova's Chinese Restaurant: Book Club

The art of book five in Anthony Powell's dodecologic Dance to the Music of Time

Once you’re in the grip of Dance you start to see echoes of its central theme everywhere. I’m rereading Arnold Bennett’s excellent novel The Card at the moment and came across this:

Every life is a series of coincidences. Nothing happens that is not rooted in coincidence. All great changes find their cause in coincidence.

Of course there are coincidences again in Casanova’s Chinese Restaurant - the obligatory unexpected/expected bump into Widmerpool, the delightful reemergence of Charles Stringham - but there are plenty of new folk to welcome to the Dance too. Here’s what Powell himself said about the book in his 1989 journals (if you’re getting the Powell bug I’d heartily recommend them, they come in three very readable volumes) during his complete reread through that year:

Good beginning to Casanova, but overlong explanatory passages follow, probably unavoidable to establish new characters and changing atmosphere of the period. At same time all rather lacking in action until Mrs Foxe’s party, visit to Maclintick, his death, events leading up to these, both episodes satisfactorily dramatic after rather long somewhat rambling descriptions.

I’d agree with that, though it’s interesting he doesn’t mention the theme of marriage which runs throughout the book (I personally believe he missed a trick in not devoting a passage to Nick’s wedding which I think would have been very entertaining).

It’s also one of the novels in the series which is most dominated by art, one of Powell’s great interests, which is marvellous unless the readers are unfamiliar with his references, so what I’m going to do here is whizz through a few of the real life highlights.

The book starts with both a literal and literary framing - Moreland is introduced then discussed and finally given a brief eulogy, while Nick observes the ruins of The Mortimer pub “pondering the mystery which dominates vistas framed by a ruined door”. Powell was fascinated with ruins and what emotions they evoked in people. In a review of Rose Macaulay’s 1953 book Pleasure of Ruins he noted that “there is something inherently beautiful in ruined shapes”. It’s a theme that crops up again in future books in the series.

So, starting with the idea of time which is at the heart of the whole shooting match, the image at the top of this page is a detail from Bronzino’s sexually explicit-ish Allegory with Venus and Cupid, with Father Time at the top and just below him a youthful portrayal of Folly - he’s about to step on a thorn - which Nick uses to describe Moreland (“his short, dark, curly hair recalled a dissipated cherub, a less aggressive, more intellectual version of Folly in Bronzino’s picture”).

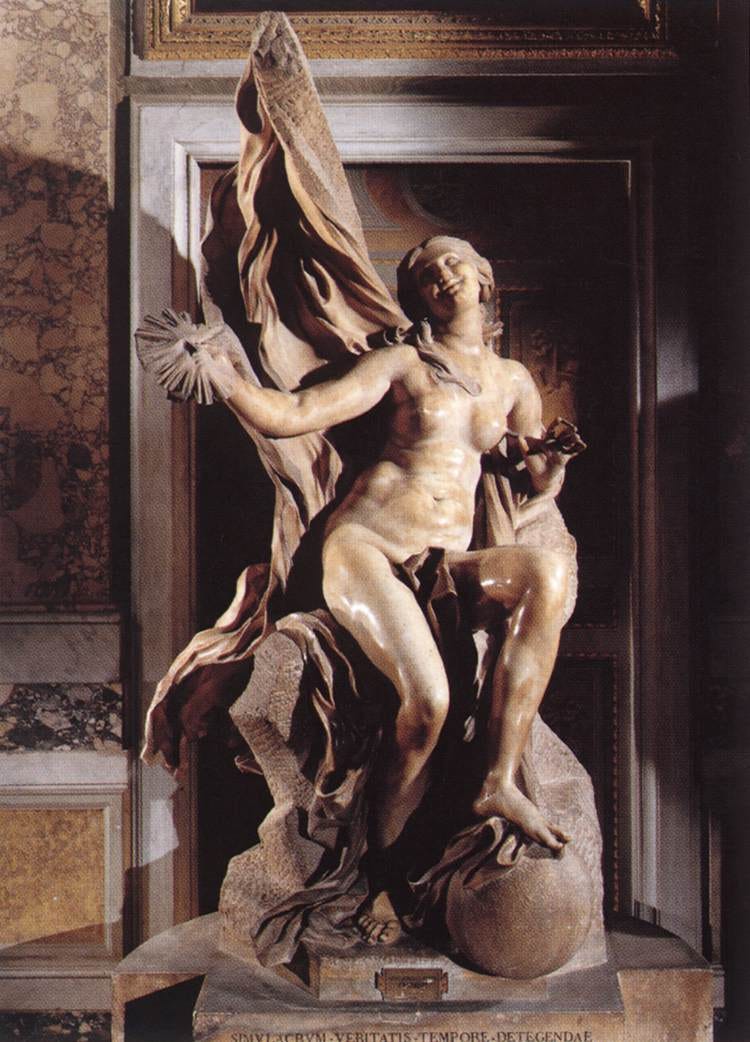

And here is the original, probably unfinished, Bernini sculpture of Truth Unveiled by Time, a copy of which Mr Deacon is considering buying in the pub and which turns up later in Mrs Foxe’s house:

Back to Moreland in whose flat hang various caricatures by the Legat brothers, choreographer Nikolai and dancer Sergei, whose book of caricatures of the great and good of the Russian ballet world he breaks up to decorate the walls. Here’s their Anna Pavlova:

The inside of Casanova’s itself is harder to pin down. Moreland describes the interior as “decoration French eighteenth century - some way, some considerable way, after Watteau”. As a flavour, here’s the kind of thing he was perhaps thinking about, The Love Lesson by Jean-Antoine Watteau (1684 – 1721):

And how about the waitress that Barnby takes a shine to in Casanova’s? When he says he wants to paint her portrait, Moreland says he likes “an academic, even pedestrian, naturalism of portraiture” because “Nothing I’d care for less than to have my girl painted by Lhote or Gleizes”. Both had a similar approach so here’s an example of Albert Gleizes’s work, Femme et enfant, painted around the time the late 1920s action in CCR takes place:

Lots of artists get brief name checks, Braque, Dufy, Gozzoli, Picasso, as well as more vaguely 18th century French engravings and the London Group retrospective which Barnby says he has just popped in to see. So let’s finish with the catalogue cover of that very exhibition, designed by Allan Walton.

Get ready for another major flashback as we head towards book six, The Kindly Ones. In the meantime, please enjoy the mighty Peter Dawson singing the Kashmiri Song or Pale Hands I Loved Beside The Shalimar by Violet Nicolson and Amy Woodforde-Finden which Nick hears and sets him off on a search for lost time at the start of the book.

This sentimental ballad was published in 1903 and it immediately became a symbol of the ‘exotic Orient’ and hugely popular over the next 40 years. Major artists apart from Dawson recorded it, and it appeared in various films including Hers to Hold (1943) sung by leading star of 1940s musicals Deanna Durbin, and frequently found its way into many books from Bertie Wooster singing it in the bath in Jeeves and the Feudal Spirit (1954) to Vikram Seth’s A Suitable Boy (1994).

Thank you Alex for your thoughtful analysis. I am tolerably interested in Art but, I must admit, never heard of Llote or Glaizes. On what you showed I don’t think that I would want a portrait painted by either of them. I must look them up.

There is definitely a gathering gloom running through the book and we, of course, know what’s coming. McClintick’s suicide at the end of the book contributes to the atmosphere.

I do agree that more about Nick’s wedding would have been interesting but I suppose he is simply keeping himself in the background as narrator. He doles out snippets about his private life from time to time, like the arrival of the baby, but doesn’t elaborate.

In preparation for The Kindly Ones I listened to Peter Dawson singing the Kashmiri song - I expected it to sound familiar but I don’t think I’ve ever heard it before.

I’m glad you like The Card - very different from most of Arnold Bennett but such a good read. I have recommended it to many over the years and sometimes sent people a copy when they said they hadn’t read it.

Casanovas Chinese Restaurant

As always your commentary illuminates aspects of the book I hadn’t focused on. Watteau’s The Love Lesson made me think immediately of the old Sagne cafe on Marylebone High Street, which had dreamy trompe d’oeil interiors -now all swept away. I found a picture of Lucien Freud supping there with his mother in the 80s. In those days it was beloved of Harley St doctors, RAM musicians and genteel ladies such as myself with a penchant for afternoon tea. Perhaps it was Powell’s inspiration. And I couldn’t help imagining The Mortimer pub as The Wheatsheaf in Rathbone Place - never bombed as far as I know, but a well known haunt of Dylan Thomas and Augustus John.

I’d love to see the paintings that were exhibited in the show of the London Group!

I hope you don’t mind me adding my own thoughts (in a bit of length here).

I like the way Casanova’s starts at the end and, just like the fate of some of Nick’s friends (which we don’t learn about till later) it has been obliterated by a wartime bomb. We are invited to think that that world and that part of Nicks life is now over. But I don’t think it was!

I can’t help finding shared imagery with Waugh’s books (think of the trompe d’oiel room in Brideshead (1945)) or Decline and fall (1928), which I gather was influenced by Gibbon.

But while Gibbon describes the decline and eventual obliteration of Roman civilisation - serious stuff and Waugh treated the whole 30s decline as a bit of a joke, Powell’s characters are more nuanced and suffer a variety of fates. One commits suicide, triggering another to leave his mistress to go back to his wife. Erridge is left money - enabling him to do the right thing by his family and Nick stands always at the centre of the maelstrom, observant, uncritical and unscathed.

Casanovas is described as East meets West, present and past, incongruous - an amalgam of cultures, just as Nick’s circle encompass business and the arts, straight and gay, rich and poor. I like the way old friends like Deacon, St John Clarke and Mackintosh represent the ‘old school’ the past while Moreland, Erridge and women like the Tolland sisters represent a future, albeit one that is about to be sorely tested.

I noticed the deliberate ambivalence that Powell shows to his characters who are often contradictory. This is personified in Matilda, who turns out to be complex in character and looks. She is described as unconventionally beautiful, a ‘jolie laide’. I had to look it up, roughly translated it means ‘pretty ugly’ - striking or unconventional - I imagine a twiggy or a Grace Jones, not a Mia Farrow.

Nobody is sainted or condemned in the book. Even the most feckless of characters are treated even handedly. is there a tinge of guilt here One wonders whether Powell himself, who married Lady Violet Pakenham in 1934 left a few skeletons in his own cupboards at that time? Though I’m not aware of any.

The balance of humour and drama is skilful. The one heightens the other. As the book progresses and the prospect of war looms the mood certainly darkens. Nick’s rather hapless bohemian friends are treated with humour, but the suicide of a fellow music critic brings Nick and Moreland to their senses.

I found the decline and fall of Maclintick to be unexpectedly sombre and sad. He becomes a metaphore for the pre-war ‘carefree’ bohemians who we will not see again until the 60s.

There is probably recognition that the old world is probably best left behind.

The book ends with the metaphor of the ghost train, which pitched and turned its passengers this way and that, both fast and slow towards ‘a shape that lay across the line’. That spectre is certainly the Second World War.

Thank you and looking forward to next month