Just before Christmas I’ll be going to a major reunion of friends from university, some of whom I haven’t seen for 30 years. Doubtless, chitchat will initially revolve around what we’ve all been wasting our time on in the intervening decades and when I say that I am now a writer I will inevitably be asked what I write about. It’s the first question almost everybody asks when they found out I scribble for a living and is completely understandable. But I don’t have a quick and easy answer.

The thing is that I don’t really have a specialty. Rather than sensibly focusing all my efforts towards the English Civil War, horticulture, or ghosting celebrity sportspeople’s memoirs, my backlist is, to put it politely, wide ranging. So I have written several books about what might be termed “book culture” (The Book Lover’s Almanac, The Book Lover’s Joke Book, Rooms of Their Own, How to Give Your Child a Lifelong Love of Reading, Edward Lear and the Pussycat: Famous Writers and Their Pets, Shelf Life, Book Towns, A Book of Book Lists, Improbable Libraries, and Bookshelf). That’s usually the answer I give, but it’s only partially true.

Because I’ve also written a couple on sheds (Haynes Shed Manual and Shedworking), food (Menus That Made History), one on classical music (A Soundtrack to Life), two on art (Studios of Their Own and Art Day by Day: 366 Brushes with History), and one about weather (100 Words for Rain).

What then links all these? The apparent randomness of the list is not simply an inability to say no to anything I’m offered. Rather, I enjoy moving between subjects and then, in the nicest possible way, moving away rapidly from them again. I suspect this is the trained journalist in me, the thrill of getting up to speed very fast on a topic and then careering off suddently in a totally different direction once the job is finished.

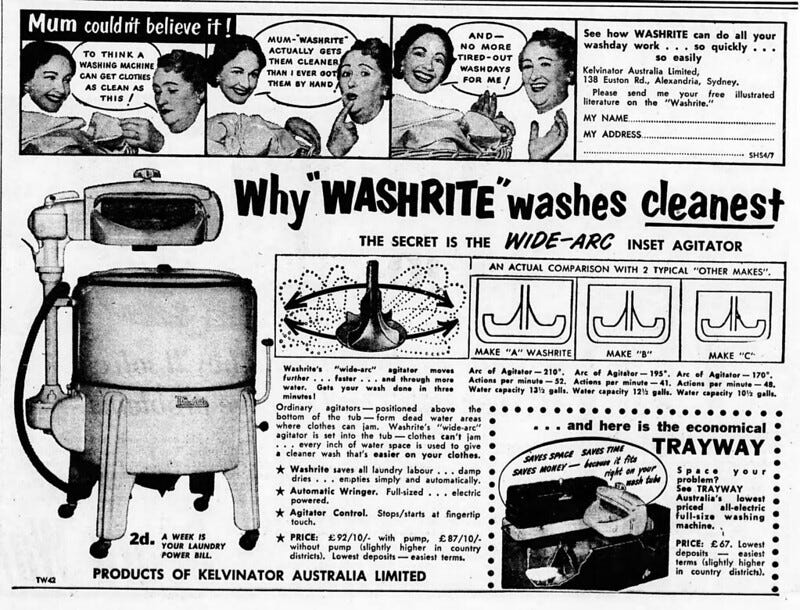

As a journalist though, the stories largely came to me, I didn’t select them. As a writer, what I do is write about what I like. I am interested in books, sheds, art, music, food, and the weather. I’m hoping to add ‘sport’ to the list and write one about snooker next year. If I were asked to write a book about washing machines, unless the advance was unturndownable, I’d decline. I’m not deriding them, I just personally do not want to spend a year thinking about little else than washing machines. I do want to spend a year writing about the pleasures of the baize.

This then is one of the key things I always tell people who ask me what they should write about (sometimes I tell them even if they don’t ask me) - write what you know maybe, but definitely write what you like. And, as the newspapers are so annoyingly wont to say nowadays, here’s why.

Samuel Johnson’s mid-18th century column The Idler in the weekly Universal Chronicle is still a wonderful read today. But not all the 103 essays printed under the annoymous Idler byline were by Johnson. The artist Joshua Reynolds wrote a couple on painting and Poet Laureate Thomas Warton also contributed several on various topics concerning virtue and the dangers of too much indolence. But one of my favourites was by the fascinating if now largely forgotten Bennet Langton.

Langton (1736 – 1801) was a close friend of Johnson’s, a founding member of his Literary Club, rather thin and extremely tall for the day, probably around the 6ft 6in mark (not many men could literally look down on Johnson who stood an imposing 6ft-ish high himself). He was also smart and friendly. Johnson’s biographer James Boswell described him as possessing an “inexhaustible fund of entertaining conversation” and the philosopher and statesman Edmund Burke, a fellow Club member, observed that women “gathered round him like maids round a maypole”. He was also the man who proposed to the MP William Wilberforce at a dinner party held in his own home that he should campaign for the abolition of slavery in Parliament. At the same time, according to Boswell, he had no interest in the financial management of his estates and couldn't really be bothered to keep proper accounts.

This more languid side of Langton is on show in the glorious July 1759 piece he contributed to The Idler, number 67, entitled Scholar’s Journal when the essays were eventually collected into book form.

The conceit is that Langton has come across the diary of a scholarly chap and is presenting it to the readers. The scholar confides to his journal that he plans to spend the following three days in deep study, “to finish my Essay on the Extent of the Mental powers; to revise my Treatise on Logick; to begin the Epick which I have long projected; to proceed in my perusal of the Scriptures with Grotius’s Comment; and at my leisure to regale myself with the works of classicks, ancient and modern, and to finish my Ode to Astronomy.”

An optimistic workload indeed as is proven on day one, Monday, when he plans to get up at 6am, but snoozes until 9am (there but for the grace of God…). When he finally gets down to business after breakfast at 10am, the scholar is distracted from writing his essay when he consults Plato’s Republic which he finds much more interesting and reads instead. He then goes for a coffee with a friend, followed by a tavern, a mooch around town, a walk in the park, and so the rest of the day runs away from him.

Much the same kind of thing happens to him on Tuesday. And Wednesday. Though - and this is the key takeaway - he does find time over the three days to enjoy writing some unplanned poetry.

The moral? You actually get more done when you concentrate on what you’re actually interested in. Or as he puts it far more elegantly:

“this one position, deducible from what has been said above, may, I think, be reasonably asserted, that he who finds himself strongly attracted to any particular study, though it may happen to be out of his proposed scheme, if it is not trifling or vicious, had better continue his application to it, since it is likely that he will, with much more ease and expedition, attain that which a warm inclination stimulates him to pursue, than that at which a prescribed law compels him to toil.”

The two men remained firm friends until Dr Johnson’s death in 1784 (Langton was one of the six pall bearers at Johnson’s funeral in Westminster Abbey). In his will, he appointed Langton, who was nearly 30 years younger than him, in charge of distributing £750 to Johnson’s close friends - plus a £70 annuity to his Jamaican servant Francis Barber - and more personally bequeathed him several books including Johnson’s Polyglot Bible and some Latin poems.

It was a mark of the man that Langton sold some of these to London booksellers (he also gave some to King George III who in turn passed them on to the British Museum) and gave the proceeds to a relative of Johnson’s who had not been named in his will.

Which is all a longwinded way of saying that if you haven’t fancied the look of any of the books I’ve written so far, don’t worry, there will be more leaping off the production line next year which might be more your cup of tea (literally so…).

I think you should maybe reconsider your decision not to pursue the ‘laundry’ genre. Judging by Procter and Gamble’s share price, there could be money in it.

Excellent description of the seeming randomness of someone’s output.

(And I laughed at “tell them even if they didn’t ask”)